Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms

330 likes | 1.11k Views

Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms. Katherine B. Harrington Vascular Surgery Conference May 15, 2006. Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms. Uncommon, but clinically important 22% present emergently, with an overall mortality of 8.5%.

Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms Katherine B. Harrington Vascular Surgery Conference May 15, 2006

Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms • Uncommon, but clinically important • 22% present emergently, with an overall mortality of 8.5%. • Incidence is increasing as imaging improves, but distribution is constant. • One-third will have associated nonvisceral aneurysms as well- aortic, renal, iliac, lower extremity, and cerebral.

Splanchnic Aneurysm Treatment • Although noninvasive imaging is improving, selective arteriography is the mainstay for planning therapy. • Surgery is still considered the gold standard especially for emergent rupture but both prophalactic and post-rupture catheterization are gaining in popularity. • Consistent long term results are lacking e.g: -Study 1: 92% early success rate, 4% mortality at 1 month, and only 1 recurrence at 4 years. vs. -Study 2: 57% early success rate, convert to open in 20%. • Catheter based interventions more appropriate for those aneurysms involving solid organs, e.g. those embedded in hepatic or pancreatic tissue with well formed collaterals.

Splenic Artery Aneurysms • Incidence: -Necropsy series vary between 0.098% to 10.4%. -0.78% on review of abdominal arteriographic studies. -Female to male ratio of 4:1. • Pathophysiology: -Saccular macroaneurysms secondary to acquired derangements of vessel wall: elastic fiber fragmentation, loss of smooth muscle, and internal elastic lamina disruption. -Occur most often at bifurcations. -Multiple in 20% of patients.

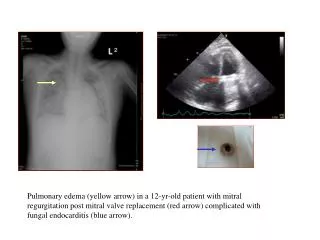

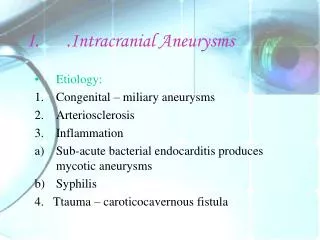

Splenic Aneurysms: Risk Factors • Fibromuscular Dysplasia: • Those with renal dysplasia are 6x more likely to have splenic aneurysm. • Portal Hypertension with Splenomeglay: • Splenic Aneurysms found in 10-30% of patients. • Often multiple aneurysms. • Multiple Pregnancies: • 40-45% of female patients in case series were grand multiparous • Thought to be secondary to both hormonal effects and increased splenic arteriovenous shunting during pregnancy. • Other: • Nearby inflammation: e.g. chronic pancreatitis -> false aneurysms. • Mycotic aneurysms from endocarditis from IVDA. • Trauma.

Splenic Aneurysms: Presentation • History: • 17-20% symptomatic with vague LUQ pain with occasional radiation. • 3-9.6% Rupture: Normally bleeds into lesser sac with CV collapse. • 25% of ruptures get “Double rupture phenomenon” when blood escapes lesser sac confinement. Provides window for treatment. • Ruptures can also present as GI bleeding or arteriovenous fistulas. • Exam: • -- Bruit rare. • Normally under 2cm, so rarely • palpable pulsatile mass. • Imaging/Labs: • Often found incidentally with • CT/MRI/Arteriography. • 70% will have curvilinear, signet • ring calcification on Xray. • MMP-9 for monitoring progression.

Splenic Aneurysm: Treatment Indications • Indications for Treatment: • Symptomatic Aneurysms • Aneurysms > 2 cm. • OLT patients: mortality post rupture >50%. • Pregnant patients or those who want to conceive: • Maternal mortality post rupture –70%, fetus- 75%. • Not associated with increased risk for rupture: • Calcifications • Age >60 • Hypertension.

Splenic Aneurysms: Treatment Options • Aneurysmectomy, Aneursymorraphy, Simple ligation-exclusion without arterial reconstruction. Restoration of splenic artery continuity is rarely indicated. • Endovascular Coiling-still with unsure failure rates, risk of splenic infarction. • Stent Grafting- rare when splenic flow is needed for other theraputic reason like mesocaval shunting.

Splenic Aneurysm: Treatment • Proximal Aneurysms: • Excise Gastrohepatic ligament. • Expose through lesser sac. • Ligate entering and exiting vessels. • Those not embedded in pancreatic tissue are excised. • Mid-Splenic Aneurysms: • Generally associated with pancreatitis- generally false aneurysms. • Clamp proximal splenic artery. • Ligate arteries with prolene from within aneurysmal sac to reduce infection. • Placement of external drains in associated psuedocysts. • May need distal pancreatectomy. • Peri-Hilar: • Conventionally treated by splenectomy. • Now simple suture obliteration, aneurysmorraphy, or excision recommended.

Hepatic Artery Aneurysms • Incidence: • 20% of splanchnic aneurysms. • 1/3 associated with splenic aneurysms. • Male: Female 2:1. • Most common in patients in their 50s. • Normally solitary • Average >3.5 cm. Those >2cm tend to be saccular. • 80% Extrahepatic, 20% intrahepatic. • Common hepatic: 63% • Right hepatic: 28% • Left Hepatic 5% • Right and Left hepatic: 4%.

Hepatic Artery Aneurysms • Etiology: • Medial degeneration- 24%. • False aneurysms secondary to trauma- 22% • Infectious (IVDA)- 10% • Oral amphetamine use- ? • Periarterial inflammation, e.g. cholecystitis or pancreatitis- rare.

Hepatic Aneurysms: Presentation • Most likely asymptomatic. • Can present as RUQ or epigastric pain +/- radiation to the back not associated with meals. • Manifest as extrahepatic bile duct obstruction when large aneurysms compress biliary tree. • Pulsatile masses and bruits rare. • Rupture risk ~20-44%. Mortality > 35%. • Rupture: into hepatobiliary tract and peritoneal cavity with equal frequency. • Rupture into bile ducts produces hematobilia- colic pain, massive GI bleeding with hematemesis, jaundice, and fevers are common. More common with traumatic intrahepatic false aneurysms. • Rupture into peritoneal cavity produced acute abdomen, CV colapse. More likely in PAN associated aneurysms.

Hepatic Aneurysms: Treatment • Common Hepatic Artery: • Extensive collaterals allow aneurysmectomy or exclusion without reconstruction. • However, 5 minute occlusion trial recommended to confirm flow to prevent necrosis. • Those with already existing parenchymal disease may need reconstruction.

Hepatic Aneurysms: Treatment • Proper Hepatic Artery and Extrahepatic branches: • Requires revascularization. • Subcostal or vertical midline incision. • Care should be taken to avoid common bile duct injury near the proximal hepatic artery near the gastroduodenal artery and pancreaticoduodenal artery.

Hepatic Aneurysm: Repair options • Aneurysmorrhaphy with or without vein patch closure, especially for traumatic false aneurysms. • Resection and reconstruction for fusiform or saccular with interpostion grafts using autogenous saphenous vein. Use spatulation of the artery and vein graft to produce ovoid anastomoses. • Aortohepatic bypass when interpostion not possible: • Extended Kocher manuver, medial viseral rotation. • Vein graft from aorta behind duodenum to porta hepatis. • Spatulated vein to artery with end-to-end anastomosis. • Liver parenchymal resection for intrahepatic aneurysms nonamenable to resection. • Endovascular coiling especially for traumatic- but with 42% recanulization reported.

Superior Mesenteric Artery Aneurysms • 5.5% of all splanchnic aneurysms. • Affects men and women equally. • Affects the first 5cm of the SMA. • Most often infectious in etiology: Nonhemolytic Strep- related to Left sided endocarditis. • Dissecting aneurysms are rare, but more common than in other visceral aneurysms. • Trauma- rare cause.

SMA Aneurysm: Presentation • Most are symptomatic • Intermittent upper abdominal pain progressing to constant epigastric pain. • Half of patients have a tender pulsatile mass that is not rigidly fixed. • Dissection or propagation can cause intestinal angina. • 40% Rupture rate.

SMA Aneurysm: Treatment • Aneursymorrhaphy or simple ligation without reconstruction is acceptible, but try temporary occlusion of SMA with assesment of bowel viability. • Aneursymectomy hazardous secondary to surrounding SMV and pancreas. • Distal lesions through transmesenteric route. Proximal lesions visualized through retroperitoneal. • Interpostition graft or aortomesenteric bypass after exclusion is rarely accomplished/done. • Transcatherter occulsion used, but stent-grafts generally not favored secondary to high infectious etiology percentage.

Celiac Artery Aneurysms • Equal sex predilection. 50’s. • Mostly medial degeneration related. Trauma and infection rare. • Most are asymptomatic. • Bruits heard frequently, and palpable puslatile mass in 30%. • Risk of rupture 13%. Normally intraperitoneal.

Celiac Aneurysms: Treatment • Aneursymectomy with aortoceliac bypass with graft originating from supraceliac aorta, or aneurysmectomy with primary reanastomosis. • OR celiac axis ligation. Do not use with liver dx. • Abdominal route, medial visceral rotation, transection of crus and median arcuate ligament to expose celiac. If celiac is particularly large may need a thoracoabdominal approach.

Gastric and Gastroepiploic Aneurysms • Likely etiology medial degeneration. • Often solitary • Gastric artery aneurysms are 10x more common than gastroepiploic. • Men:Women 3:1. 50s and 60s. • Over 90% present as ruptures with 70% with serious GI bleeding. Very few admit to preceding symptomatology.

Gastric and Gastroepiploic Aneurysms- Treatment • Treatment directed at stopping the hemorrhage- approximately 70% mortality post-rupture. • Ligation with or without excision of aneurysm is appropriate for extraintestinal lesions. • Intramural aneurysms and those bleeding into the GI tract should be excised with the portions of associated gastric tissue.

Jejunal, Ileal, and Colic Aneurysms • Pathogenesis poorly understood. • Equal sex distribution. 60s. • Most are solitary, mms to 1cm. • Multiple lesions seen with immunologic injury, septic emboli, or necrotizing vasculitides. • Rarely symptomatic. • Jejunal rupture rare, colic rupture more common. • 20% rupture mortality.

Jejunal, Ileal, and Colic Aneurysms:Treatment • Arterial ligation, aneurysmectomy, and resection of affected bowel if blood supply is compromised.

Gastroduodenal, Pancreaticoduodenal, and Pancreatic Aneurysms • Gastroduodenal aneurysms are 1.5% of splanchnic aneurysms and pancreaticoduodenal and pancreatic are 2%. • Men:Female is 4:1. • Etiology: Periarterial inflammation, actual vascular necrosis, and erosion by expanding pancreatic psuedocysts. False aneurysms more common. • 60% present as rupture, with a 49% mortality. • Most are symptomatic with epigastric pain radiating to back, because most are pancreatitis related. • 75% tend to have GI bleeding into stomach or duodenum.

Gastroduodenal, Pancreaticoduodenal, and Pancreatic Aneurysms • Treatment: Pancreaticoduodenal and pancreatic artery aneurysms are more difficult to treat secondary to their small size and being embedded in the pancreas. Intraoperative arteriography is useful. • Suture ligature of entering and exiting vessels without extra-aneurysmal dissection is appropriate. • Those involving pancreatic tissue should place appropriate drains and/or resection pancreatic tissue as needed. • Transcatheter embolization has been described, but may only serve as a temporizing step. • Stent-grafting of the SMA which occludes the pancreaticoduodenal has also been described.