Development of Effective Memory Strategies in Children and Adults

10 likes | 101 Views

This study investigates the impact of deep encoding strategies on associative memory development from childhood to adulthood. Findings show that belief in strategy effectiveness and strategy selection play crucial roles in memory performance across age groups.

Development of Effective Memory Strategies in Children and Adults

E N D

Presentation Transcript

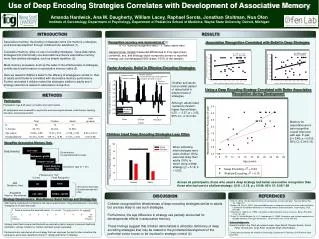

Use of Deep Encoding Strategies Correlates with Development of Associative Memory Amanda Hardwick, Ana M. Daugherty, William Lacey, Raphael Serota, Jonathan Stoltman, Noa Ofen Institute of Gerontology, Department of Psychology, Department of Pediatrics School of Medicine, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan INTRODUCTION RESULTS • Associative memory, the binding of disparate items into memory, undergoes protracted development through childhood into adulthood (1). • Successful memory relies on use of encoding strategies. Deep elaborative strategies that intentionally use associations enhance associative memory more than shallow strategies, such as simple repetition (2). • Meta-memory processes, such as the belief in the effectiveness of strategies, contributes to performance on associative memory tasks (2). • Here we tested if children’s belief in the efficacy of strategies is similar to that of adults and if belief is correlated with associative memory performance. Further, we tested if children select the strategies similar to adults and if strategy selection is related to associative recognition. Recognition accuracy was measured as d’ (3): d’ = z-1(correct recognition rate) – z-1(false alarm rate) General linear models measured differences in d’ by age (mean centered), sex, and strategy factor composite scores or reported strategy use (bootstrapped 5000 draws, 100% of the sample). Associative Recognition Correlated with Belief in Deep Strategies Factor Analysis: Belief in Effective Encoding Strategies Children and adults had a similar pattern of rating belief in effectiveness of strategies. Although, adults rated “sentence creation” higher than children: t(27) = -3.27, p = 0.02, 95% CI: -4.16/-0.99. Using a Deep Encoding Strategy Correlated with Better Associative Recognition during Development METHODS Participants Participants: Age 8-25 years; all healthy and right-handed. All participants were screened for psychiatric and neurological disease, head trauma, learning disorders, and premature birth. Memory for associative word-pair recognition overall improved with age: d’-pair, β = 0.46, p = 0.003; 95% CI: 0.04/0.15). Children Used Deep Encoding Strategies Less Often Word-Pair Associative Memory Task When indicating what strategies were used, children (55%) were less likely than adults (76%) to report using a deep strategy (χ2 = 5.16, p = 0.02). cat—rose Study Encoding 26 word-pairs; Counterbalanced list order keyboard—giraffe temper—vessel Count down by 3’s from 792 Distraction Task for 1 min. If Response is “Yes” Correct False Recognition Across all participants, those who used a deep strategy had better associative recognition than those who had used a shallow strategy: t(14) = 2.18, p = 0.046; 95% CI: 0.02/1.68 hand cat Item Studied vs. New 16 forced-choice trials; Counterbalanced test order cat—rose temper—giraffe Associative Intact vs. Recombined DISCUSSION REFERENCES Strategy Questionnaire: Meta-Memory Belief Ratings and Strategy Use 1 Ofen, N. (2012). The development of neural correlates for memory formation. Neurosci Behav Rev, 36, 1708-1717. 2 Bender, AR, Raz, N. (2012). Age-related differences in recognition memory for items and associations: Contribution of individual differences in working memory and metamemory. Psyhol Aging, 27(3), 691-700. 3 Stainslaw, H, Todorov, N. (1999). Calculation of signal detection theory measures. Behav Res Meth, 31(1), 137-149. 4 Shing, YL, Werkle-Bergner, M, Li, S, Lindenberger, U. (2008). Associative and strategic components of episodic memory: A life-span dissociation. J Exp Psychol Gen, 137(3), 495-513. Acknowledgments Special thanks to the OfenLab research team: Ryan Abbott, Raagini Suresh, Komal Patel, Tanvee Jain, Ishan Patel, Sunpreet Singh, Nikhil Adapa. Funding was provided by the Institute of Gerontology, Department of Pediatrics, OVPR Wayne State University. • After testing, participants completed a self-report questionnaire, rating effectiveness of encoding strategies on a Likert item scale: • Strategy belief factors were identified with an exploratory factor analysis (maximum likelihood estimation, varimax rotation) for children and adult groups separately. • Participants also reported what one strategy that was used was the best to later remember the word-pairs, which was classified as Factor 1 (Deep) and Factor 2 (Shallow). • Children recognized the effectiveness of deep encoding strategies similar to adults but are less likely to use such strategies. • Furthermore, the age difference in strategy use partially accounted for developmental effects in associative memory. • These findings suggest that children demonstrate a utilization deficiency of deep encoding strategies that may be related to the protracted development of the prefrontal cortex known to be involved in strategic control (4). • 1. Create a sentence that uses both words. For example: “The giraffe typed on the keyboard.” • 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 • Least Most • Effective Effective