Charles Lindbergh

241 likes | 322 Views

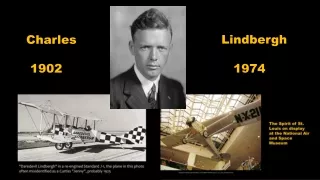

History about Charles Lindbergh, born 1902, dead 1974.

Charles Lindbergh

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Lindbergh Charles 1974 1902

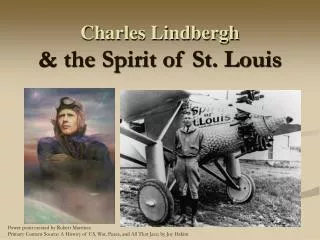

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. At the age of 25 in 1927, he went from obscurity as a U.S. Air Mail pilot to instantaneous world fame by winning the Orteig Prize for making a nonstop flight from New York City to Paris. Lindbergh covered the 33 1⁄2-hour, 3,600-statute-mile (5,800 km) flight alone in a purpose-built, single-engine Ryan monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis. Although not the first non-stop transatlantic flight, this was the first solo transatlantic flight, the first transatlantic flight between two major city hubs, and the longest transatlantic flight by almost 2,000 miles, thus it is widely considered a turning point in the development of aviation.

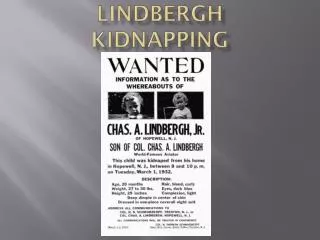

Lindbergh was an officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve, and he received the United States' highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his transatlantic flight. His achievement spurred interest in both commercial aviation and air mail, which revolutionized the aviation industry, and he devoted much time and effort to promoting such activity. In March 1932, Lindbergh's infant son, Charles Jr., was kidnapped and murdered in what the American media called the "Crime of the Century". The case prompted the United States Congress to establish kidnapping as a federal crime if the kidnapper crosses state lines with a victim. By late 1935, the hysteria surrounding the case had driven the Lindbergh family into exile in Europe, from which they returned in 1939.

In the years before the United States entered World War II, his non-interventionist stance and statements about Jews led some to suspect he was a Nazi sympathizer, although Lindbergh never publicly stated support for Nazi Germany. He opposed not only the intervention of the United States, but also the provision of aid to the United Kingdom. He supported the anti-war America First Committee and resigned his commission in the U.S. Army Air Forces in April 1941 after President Franklin Roosevelt publicly rebuked him for his views. In September 1941, Lindbergh gave an address stating that the British, the Jews and the Roosevelt administration were the "three most important groups" pressing for greater American involvement in the war. He also said capitalists, intellectuals, American Anglophiles, and Communists were all agitating for war.

Lindbergh publicly supported the U.S. war effort after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent German declaration of war against the United States. He flew 50 missions in the Pacific Theater of World War II as a civilian consultant, but did not take up arms against Germany, and Roosevelt refused to reinstate his Air Corps colonel's commission. In his later years, Lindbergh became a prolific author, international explorer, inventor, and environmentalist.

Lindbergh was born in Detroit, Michigan on February 4, 1902 and spent most of his childhood in Little Falls, Minnesota and Washington, D.C. He was the third child of Charles August Lindbergh (birth name Carl Månsson; 1859–1924) who had emigrated from Sweden to Melrose, Minnesota as an infant, and his only child with his second wife, Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh (1876–1954), of Detroit. Charles' parents separated in 1909 when he was seven.[6] Lindbergh's father, a U.S. Congressman (R-MN-6) from 1907 to 1917, was one of the few Congressmen to oppose the entry of the U.S. into World War I (although his Congressional term ended one month prior to the House of Representatives voting to declare war on Germany). His book, Why Is Your Country at War, which criticized the US' entry into the first World War, was seized by federal agents under the Comstock Act. It was later posthumously reprinted and issued in 1934, under the title Your Country at War, and What Happens to You After a War

Lindbergh's mother was a chemistry teacher at Cass Technical High School in Detroit and later at Little Falls High School, from which her son graduated on June 5, 1918. Lindbergh also attended over a dozen other schools from Washington, D.C., to California, during his childhood and teenage years (none for more than a year or two), including the Force School and Sidwell Friends School while living in Washington with his father, and Redondo Union High School in Redondo Beach, California, while living there with his mother. Although he enrolled in the College of Engineering at the University of Wisconsin– Madison in late 1920, Lindbergh dropped out in the middle of his sophomore year and then went to Lincoln, Nebraska, in March 1922 to begin flight training.

Early aviation career From an early age, Lindbergh had exhibited an interest in the mechanics of motorized transportation, including his family's Saxon Six automobile, and later his Excelsior motorbike. By the time he started college as a mechanical engineering student, he had also become fascinated with flying, though he "had never been close enough to a plane to touch it. After quitting college in February 1922, Lindbergh enrolled at the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation's flying school in Lincoln and flew for the first time on April 9, as a passenger in a two-seat Lincoln Standard "Tourabout" biplane trainer piloted by Otto Timm. A few days later, Lindbergh took his first formal flying lesson in that same machine, though he was never permitted to solo because he could not afford to post the requisite damage bond. To gain flight experience and earn money for further instruction, Lindbergh left Lincoln in June to spend the next few months barnstorming across Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana as a wing walker and parachutist. He also briefly worked as an airplane mechanic at the Billings, Montana, municipal airport

"Daredevil Lindbergh" in a re-engined Standard J-1, the plane in this photo often misidentified as a Curtiss "Jenny", probably 1925

Lindbergh left flying with the onset of winter and returned to his father's home in Minnesota. His return to the air and first solo flight did not come until half a year later in May 1923 at Souther Field in Americus, Georgia, a former Army flight training field, where he had come to buy a World War I surplus Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" biplane. Though Lindbergh had not touched an airplane in more than six months, he had already secretly decided he was ready to take to the air by himself. After a half-hour of dual time with a pilot who was visiting the field to pick up another surplus JN-4, Lindbergh flew solo for the first time in the Jenny he had just purchased for $500.[17][18] After spending another week or so at the field to "practice" (thereby acquiring five hours of "pilot in command" time), Lindbergh took off from Americus for Montgomery, Alabama, some 140 miles to the west, for his first solo cross- country flight.

He went on to spend much of the rest of 1923 engaged in almost nonstop barnstorming under the name of "Daredevil Lindbergh". Unlike the previous year, this time Lindbergh flew in his "own ship" as pilot. A few weeks after leaving Americus, the young airman also achieved another key aviation milestone when he made his first flight at night near Lake Village, Arkansas. 2nd Lt. Charles A. Lindbergh, USASRC March 1925 While Lindbergh was barnstorming in Lone Rock, Wisconsin, on two occasions he flew a local physician across the Wisconsin River to emergency calls that were otherwise unreachable due to flooding. He broke his propeller several times while landing, and on June 3, 1923 he was grounded for a week when he ran into a ditch in Glencoe, Minnesota while flying his father—then running for the U.S. Senate—to a campaign stop. In October, Lindbergh flew his Jenny to Iowa, where he sold it to a flying student. After selling the Jenny, Lindbergh returned to Lincoln by train.

Following a few months of barnstorming through the South, the two pilots parted company in San Antonio, Texas, where Lindbergh reported to Brooks Field on March 19, 1924, to begin a year of military flight training with the United States Army Air Service there (and later at nearby Kelly Field). Lindbergh had his most serious flying accident on March 5, 1925, eight days before graduation, when a midair collision with another Army S.E.5 during aerial combat maneuvers forced him to bail out. Only 18 of the 104 cadets who started flight training a year earlier remained when Lindbergh graduated first overall in his class in March 1925, thereby earning his Army pilot's wings and a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Air Service Reserve Corps. Lindbergh later said that this year was critical to his development as both a focused, goal-oriented individual and as an aviator. The Army did not need additional active-duty pilots, however, so immediately following graduation Lindbergh returned to civilian aviation as a barnstormer and flight instructor, although as a reserve officer he also continued to do some part-time military flying by joining the 110th Observation Squadron, 35th Division, Missouri National Guard, in St. Louis. He was soon promoted to 1st Lieutenant, and to captain in July 1926.

In the early morning of Friday, May 20, 1927, Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field, Long Island. His monoplane was loaded with 450 U.S. gallons (1,704 liters) of fuel that was strained repeatedly to avoid fuel line blockage. The fully loaded aircraft weighed 5,135 lb (2,329 kg), with takeoff hampered by a muddy, rain-soaked runway. Lindbergh's monoplane was powered by a J-5C Wright Whirlwind radial engine and gained speed very slowly during its 7:52 a.m. takeoff, but cleared telephone lines at the far end of the field "by about twenty feet [six meters] with a fair reserve of flying speed. Over the next 33 1⁄2 hours, Lindbergh and the Spirit faced many challenges, which included skimming over storm clouds at 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and wave tops at as low as 10 ft (3.0 m). The aircraft fought icing, flew blind through fog for several hours, and Lindbergh navigated only by dead reckoning (he was not proficient at navigating by the sun and stars and he rejected radio navigation gear as heavy and unreliable).

The airfield was not marked on his map and Lindbergh knew only that it was some seven miles northeast of the city; he initially mistook it for some large industrial complex because of the bright lights spreading out in all directions—in fact the headlights of tens of thousands of spectators' cars caught in "the largest traffic jam in Paris history" in their attempt to be present for Lindbergh's landing. Samples of the Spirit's linen covering A crowd estimated at 150,000 stormed the field, dragged Lindbergh out of the cockpit, and carried him around above their heads for "nearly half an hour". Some damage was done to the Spirit (especially to the fine linen, silver-painted fabric covering on the fuselage) by souvenir hunters before pilot and plane reached the safety of a nearby hangar with the aid of French military fliers, soldiers, and police. Lindbergh's flight was certified by the National Aeronautic Association based on the readings from a sealed barograph placed in the Spirit

Lindbergh received unprecedented adulation after his historic flight. People were "behaving as though Lindbergh had walked on water, not flown over it. The New York Times printed an above the fold, page-wide headline: "LINDBERGH DOES IT!" His mother's house in Detroit was surrounded by a crowd estimated at about 1,000. Countless newspapers, magazines, and radio shows wanted to interview him, and he was flooded with job offers from companies, think tanks, and universities. The French Foreign Office flew the American flag, the first time it had saluted someone who wasn't a head of state. Lindbergh also made a series of brief flights to Belgium and Great Britain in the Spirit before returning to the United States. Gaston Doumergue, the President of France, bestowed the French Légion d'honneur on Lindbergh

People seemed to think we [aviators] were from outer space or something. But after Charles Lindbergh's flight, we could do no wrong. It's hard to describe the impact Lindbergh had on people. Even the first walk on the moon doesn't come close. The twenties was such an innocent time, and people were still so religious—I think they felt like this man was sent by God to do this. And it changed aviation forever because all of a sudden the Wall Streeters were banging on doors looking for airplanes to invest in. We'd been standing on our heads trying to get them to notice us but after Lindbergh, suddenly everyone wanted to fly, and there weren't enough planes to carry them.

The Spirit of St. Louis on display at the National Air and Space Museum https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Lindbergh#/media/File:Spirit_of_St._Louis_Smithsonian.JPG

Kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. On the evening of March 1, 1932, twenty-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was abducted from his crib in the Lindbergh's rural home, Highfields, in East Amwell, New Jersey, near the town of Hopewell. A man who claimed to be the kidnapper picked up a cash ransom of $50,000 on April 2, part of which was in gold certificates, which were soon to be withdrawn from circulation and would therefore attract attention; the bills' serial numbers were also recorded. On May 12, the child's remains were found in woods not far from the Lindbergh home. The case was widely called "The Crime of the Century“ Richard Hauptmann, a 34-year-old German immigrant carpenter, was arrested near his home in the Bronx, New York, on September 19, 1934. He was convicted on February 13, sentenced to death, and electrocuted at Trenton State Prison on April 3, 1936

In Europe (1936–1939) An intensely private man, Lindbergh became exasperated by the unrelenting public attention in the wake of the kidnapping and Hauptmann trial, and was concerned for the safety of his three-year-old second son, Jon. Consequently, in the predawn hours of Sunday, December 22, 1935, the family "sailed furtively" from Manhattan for Liverpool, the only three passengers aboard the United States Lines freighter SS American Importer. They traveled under assumed names and with diplomatic passports issued through the personal intervention of Treasury Secretary Ogden L. Mills. News of the Lindberghs' "flight to Europe" did not become public until a full day later, and even after the identity of their ship became known radiograms addressed to Lindbergh on it were returned as "Addressee not aboard". They arrived in Liverpool on December 31, then departed for South Wales to stay with relatives. The family eventually rented "Long Barn" in Sevenoaks Weald, Kent. In 1938, the family moved to Île Illiec, a small four-acre island Lindbergh purchased off the Breton coast of France.

In 1938, Hugh Wilson, the American ambassador to Germany, hosted a dinner for Lindbergh with Germany's air chief, Hermann Göring and three central figures in German aviation, Ernst Heinkel, Adolf Baeumker, and Willy Messerschmitt. At this dinner Göring presented Lindbergh with the Commander Cross of the Order of the German Eagle. Lindbergh's acceptance proved controversial after Kristallnacht, an anti-Jewish pogrom in Germany a few weeks later. Lindbergh declined to return the medal, later writing, "It seems to me that the returning of decorations, which were given in times of peace and as a gesture of friendship, can have no constructive effect. If I were to return the German medal, it seems to me that it would be an unnecessary insult. Göring presenting Lindbergh with a medal on behalf of Adolf Hitler in October 1938

Although Lindbergh considered Hitler a fanatic and avowed a belief in American democracy, he seemed to state elsewhere that he believed the survival of the white race was more important than the survival of democracy in Europe: "Our bond with Europe is one of race and not of political ideology," he declared. Critics have noticed an apparent influence on Lindbergh of German philosopher Oswald Spengler. Spengler was a conservative authoritarian popular during the interwar period, though he had fallen out of favor with the Nazis because he had not wholly subscribed to their theories of racial purity. Lindbergh developed a long-term friendship with the automobile pioneer Henry Ford, who was well known for his anti-Semitic newspaper The Dearborn Independent. In a famous comment about Lindbergh to Detroit's former FBI field office special agent in charge in July 1940, Ford said: "When Charles comes out here, we only talk about the Jews

Lindbergh pro – Nazi and bigot Lindbergh said certain races have "demonstrated superior ability in the design, manufacture, and operation of machines". He further said, "The growth of our western civilization has been closely related to this superiority." Lindbergh admired "the German genius for science and organization, the English genius for government and commerce, the French genius for living and the understanding of life". He believed, "in America they can be blended to form the greatest genius of all. His message was popular throughout many Northern communities and especially well received in the Midwest, while the American South was anglophilic and supported a pro-British foreign policy. The South was the most pro-British and interventionist part of the country. In his book The American Axis, Holocaust researcher and investigative journalist Max Wallace agreed with Franklin Roosevelt's assessment that Lindbergh was "pro-Nazi". However, he found that the Roosevelt Administration's accusations of dual loyalty or treason were unsubstantiated. Wallace considered Lindbergh to be a well-intentioned but bigoted and misguided Nazi sympathizer whose career as the leader of the isolationist movement had a destructive impact on Jewish people.

Double life and secret German children Beginning in 1957, Lindbergh had engaged in lengthy sexual relationships with three women while he remained married to Anne Morrow. He fathered three children with hatmaker Brigitte Hesshaimer (1926–2001), who had lived in the small Bavarian town of Geretsried. He had two children with her sister Mariette, a painter, living in Grimisuat. Lindbergh also had a son and daughter (born in 1959 and 1961) with Valeska, an East Prussian aristocrat who was his private secretary in Europe and lived in Baden-Baden All seven children were born between 1958 and 1967. Lindbergh developed a long-term friendship with the automobile pioneer Henry Ford, who was well known for his anti-Semitic newspaper The Dearborn Independent. In a famous comment about Lindbergh to Detroit's former FBI field office special agent in charge in July 1940, Ford said: "When Charles comes out here, we only talk about the Jews."

Death Lindbergh's grave in Kipahulu, Maui, Hawaii. The epitaph "If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea" is from Psalm 139:9. Lindbergh spent his last years on the Hawaiian island of Maui, where he died of lymphoma on August 26, 1974, at age 72. He was buried on the grounds of the Palapala Ho'omau Church in Kipahulu, Maui. His epitaph, on a simple stone following the words "Charles A. Lindbergh Born Michigan 1902 Died Maui 1974", quotes Psalm 139:9: "... If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea ... C.A.L.